Week 2 [Mon, Jan 20th] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Given this is a first course in SE, tradition demands that we start by defining the subject. However, let's not spend a lot of time going through lengthy/formal definitions of SE. Instead, let's look at an extract from the very first chapter of a very famous SE book, with the aim of providing some inspiration, but also an appreciation of the challenges ahead.

Can explain pros and cons of software engineering

The following description of the Joys of the Programming Craft was taken (and emphasis added) from Chapter 1 of the famous book The Mythical Man-Month, by Frederick P. Brooks.

Why is programming fun? What delights may its practitioner expect as his reward?

First is the sheer joy of making things. As the child delights in his mud pie, so the adult enjoys building things, especially things of his own design. I think this delight must be an image of God's delight in making things, a delight shown in the distinctness and newness of each leaf and each snowflake.

Second is the pleasure of making things that are useful to other people. Deep within, you want others to use your work and to find it helpful. In this respect the programming system is not essentially different from the child's first clay pencil holder "for Daddy's office."

Third is the fascination of fashioning complex puzzle-like objects of interlocking moving parts and watching them work in subtle cycles, playing out the consequences of principles built in from the beginning. The programmed computer has all the fascination of the pinball machine or the jukebox mechanism, carried to the ultimate.

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the nonrepeating nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

Finally, there is the delight of working in such a tractable medium. The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by the exertion of the imagination. Few media of creation are so flexible, so easy to polish and rework, so readily capable of realizing grand conceptual structures....

Yet the program construct, unlike the poet's words, is real in the sense that it moves and works, producing visible outputs separate from the construct itself. It prints results, draws pictures, produces sounds, moves arms. The magic of myth and legend has come true in our time. One types the correct incantation on a keyboard, and a display screen comes to life, showing things that never were nor could be.

Programming then is fun because it gratifies creative longings built deep within us and delights sensibilities you have in common with all men.

Not all is delight, however, and knowing the inherent woes makes it easier to bear them when they appear.

First, one must perform perfectly. The computer resembles the magic of legend in this respect, too. If one character, one pause, of the incantation is not strictly in proper form, the magic doesn't work. Human beings are not accustomed to being perfect, and few areas of human activity demand it. Adjusting to the requirement for perfection is, I think, the most difficult part of learning to program.

Next, other people set one's objectives, provide one's resources, and furnish one's information. One rarely controls the circumstances of his work, or even its goal. In management terms, one's authority is not sufficient for his responsibility. It seems that in all fields, however, the jobs where things get done never have formal authority commensurate with responsibility. In practice, actual (as opposed to formal) authority is acquired from the very momentum of accomplishment.

The dependence upon others has a particular case that is especially painful for the system programmer. He depends upon other people's programs. These are often maldesigned, poorly implemented, incompletely delivered (no source code or test cases), and poorly documented. So he must spend hours studying and fixing things that in an ideal world would be complete, available, and usable.

The next woe is that designing grand concepts is fun; finding nitty little bugs is just work. With any creative activity come dreary hours of tedious, painstaking labor, and programming is no exception.

Next, one finds that debugging has a linear convergence, or worse, where one somehow expects a quadratic sort of approach to the end. So testing drags on and on, the last difficult bugs taking more time to find than the first.

The last woe, and sometimes the last straw, is that the product over which one has labored so long appears to be obsolete upon (or before) completion. Already colleagues and competitors are in hot pursuit of new and better ideas. Already the displacement of one's thought-child is not only conceived, but scheduled.

This always seems worse than it really is. The new and better product is generally not available when one completes his own; it is only talked about. It, too, will require months of development. The real tiger is never a match for the paper one, unless actual use is wanted. Then the virtues of reality have a satisfaction all their own.

Of course the technological base on which one builds is always advancing. As soon as one freezes a design, it becomes obsolete in terms of its concepts. But implementation of real products demands phasing and quantizing. The obsolescence of an implementation must be measured against other existing implementations, not against unrealized concepts. The challenge and the mission are to find real solutions to real problems on actual schedules with available resources.

This then is programming, both a tar pit in which many efforts have floundered and a creative activity with joys and woes all its own. For many, the joys far outweigh the woes....

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Now, let's switch our focus to the project management aspect of SE.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to doing a software project. Those two approaches are also highly relevant to the way this course is run, and how it is different from most SE courses elsewhere.

Let's learn about those two approaches early so that we can better understand how this course works.

Can explain SDLC process models

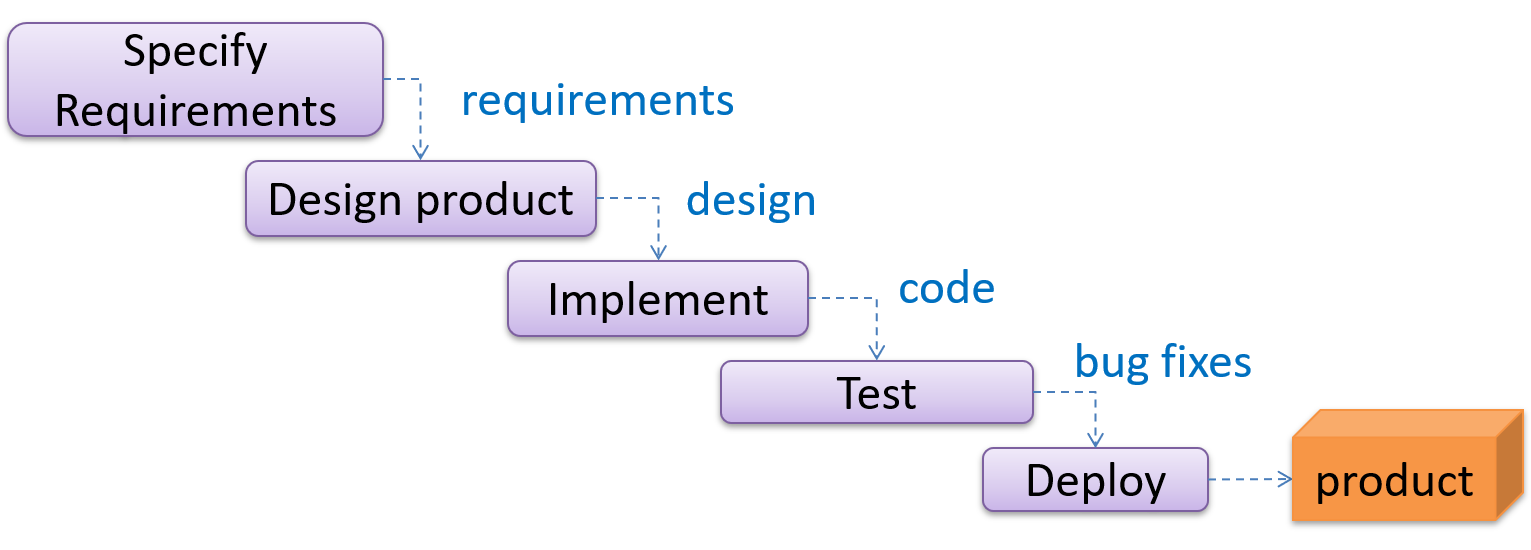

Software development goes through different stages such as requirements, analysis, design, implementation and testing. These stages are collectively known as the software development lifecycle (SDLC). There are several approaches, known as software development lifecycle models (also called software process models), that describe different ways to go through the SDLC. Each process model prescribes a 'roadmap' for the software developers to manage the development effort. The roadmap describes the aims of the development stages, the outcome of each stage, and the workflow i.e. the relationship between stages.

Can explain sequential process models

The sequential model, also called the waterfall model, views software development as a linear process, in which the project is seen as progressing through the development stages. The name waterfall stems from how the model is drawn to look like a waterfall (see below).

When one stage of the process is completed, it produces some artifacts to be used in the next stage. For example, the requirements stage produces a comprehensive list of requirements, to be used in the design phase.

A strict sequential model project moves only in the forward direction i.e., each stage is completed before starting the next. For example, once the requirements stage is over, there is no provision for revising the requirements later.

This model can work well for a project that produces software to solve a well-understood problem, in which case the requirements can remain stable and the effort can be estimated accurately. Furthermore, as each stage has a well-defined outcome, it is easy to track the progress of the project because one can gauge the project progress by monitoring which stage the project is in.

However, real-world projects often tackle problems that are not well-understood at the beginning, making them unsuitable for this model. For example, target users of a software product may not be able to state their requirements accurately at the start of the project, if they have not used a similar product before.

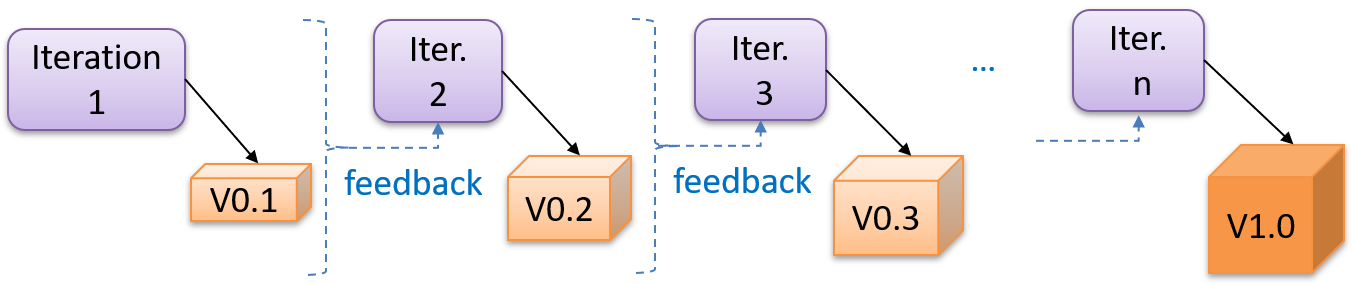

Can explain iterative process models

The iterative model advocates producing the software by going through several iterations. Each of the iterations could potentially go through all the stages of the SDLC, from requirements gathering to deployment.

Each iteration produces a new version of the product, building upon the version produced in the previous iteration. Feedback from each iteration is factored into the subsequent iterations. For example, if an implementation task took longer than expected, the effort estimate for a similar tasks in future iterations can be adjusted accordingly. Similarly, if a feature introduced in the current iteration was not well-received by target users, it can be removed or tweaked in the next iteration.

The iterative model can be done in breadth-first or depth-first approach.

- In the breadth-first approach, an iteration evolves all major components and all functionality areas in parallel i.e., most features and most will be updated in each iteration, producing a working product at the end of each iteration.

- In the depth-first approach, an iteration focuses on fleshing out only some components or some functionality area. Accordingly, early depth-first iterations might not produce a working product.

Taking a Minesweeper game as an example,

- breadth-first iterations will deliver a fully playable version early. These early versions may have primitive functionality, for example, a rudimentary text based UI, fixed board size, limited minefield layouts, etc. These functionalities (and corresponding components) will then be improved in later releases.

- an early depth-first iteration could deliver the full user interface (UI) but with no game logic at all. Alternatively, an early iteration could focus on just the logic for generating initial layouts of the minefield. Neither will be a playable version of the game but both can be used to collect early feedback (about the UI, and the initial minefield layouts, respectively) which can then be used to guide later iterations.

A project can be done as a mixture of breadth-first and depth-first iterations i.e., an iteration can contain some breadth-first work as well as some depth-first work, or, some iterations can be breadth-first while others are depth-first.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next, let's get started learning Java. First, a bit about the language itself.

This book chapter assumes you are familiar with basic C++ programming. It provides a crash course to help you migrate from C++ to Java.

This chapter borrows heavily from the excellent book ThinkJava by Allen Downey and Chris Mayfield. As required by the terms of reuse of that book, this chapter is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and not under the MIT license as the rest of this book.

Some conventions used in this chapter:

icon marks the description of an aspect of Java that works mostly similar to C++

icon marks the description of an aspect of Java that is distinctly different from C++

Other resources used:

- C++ and Java Syntax Differences Cheat Sheet by Alex Allain

- Java Tutorial provided by Oracle. Extracts from this resource are marked as -- Java Tutorial

Can explain what Java is

Java was conceived by James Gosling and his team at Sun Microsystems in 1991.

Java is directly related to both C and C++. Java inherits its syntax from C. Its object model is adapted from C++. --Java: A Beginner’s Guide, by Oracle

Fun fact: The language was initially called Oak after an oak tree that stood outside Gosling's office. Later the project went by the name Green and was finally renamed Java, from Java coffee. --Wikipedia

Oracle became the owner of Java in 2010, when it acquired Sun Microsystems.

Java has remained the most popular language in the world for several years now (as at July 2018), according to the TIOBE index.

Can explain how Java works at a higher-level

Java is both and . Instead of translating programs directly into machine language, the Java compiler generates byte code. Byte code is portable, so it is possible to compile a Java program on one machine, transfer the byte code to another machine, and run the byte code on the other machine. That’s why Java is considered a platform independent technology, aka WORA (Write Once Run Anywhere). The interpreter that runs byte code is called a “Java Virtual Machine” (JVM).

Java technology is both a programming language and a platform. The Java programming language is a high-level object-oriented language that has a particular syntax and style. A Java platform is a particular environment in which Java programming language applications run. --Oracle

Can explain Java editions

According to the Official Java documentation, there are four platforms of the Java programming language:

Java Platform, Standard Edition (Java SE): Contains the core functionality of the Java programming language.

Java Platform, Enterprise Edition (Java EE): For developing and running large-scale enterprise applications. Built on top of Java SE.

Java Platform, Micro Edition (Java ME): For Java programming language applications meant for small devices, like mobile phones. A subset of Java SE.

JavaFX: For creating applications with graphical user interfaces. Can work with the other three above.

This book chapter uses the Java SE edition unless stated otherwise.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As with any language, the first step is to install the language in your computer. After that, you write a simple HelloWorld program, and get it running.

Java 17 can be downloaded from here.

Can install Java

To run Java programs, you only need to have a recent version of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE) installed in your device.

If you want to develop applications for Java, download and install a recent version of the Java Development Kit (JDK), which includes the JRE as well as additional resources needed to develop Java applications.

Can explain the Java HelloWorld program

In Java, the HelloWorld program looks like this:

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// generate some simple output

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}

For reference, the equivalent C++ code is given below:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// generate some simple output

cout << "Hello, World!";

return 0;

}

This HelloWorld Java program defines one method named main: public static void main(String[] args)

System.out.println() displays a given text on the screen.

Some similarities:

- Java programs consists of statements, grouped , which are then grouped into classes.

- Java is “case-sensitive”, which means

SYSTEMis different fromSystem. publicis an access modifier that indicates the method is accessible from outside this class. Similarly,privateaccess modifier indicates that a method/attribute is not accessible outside the class.staticindicates this method is defined as a class-level member. Do not worry if you don’t know what that means. It will be explained later.voidindicates that the method does not return anything.- The name and format of the

mainmethod is special as it is the method that Java executes when you run a Java program. - A class is a collection of methods. This program defines a class named

HelloWorld. - Java uses squiggly braces (

{and}) to group things together. - The line starting with

//is a comment. You can use//for single line comments and/* ... */for multi-line comments in Java code.

Some differences:

- Java use the term method instead of function. In particular, Java doesn’t have stand-alone functions. Every method should belong to a class. The

mainmethod will not work unless it is inside theHelloWorldclass. - A Java class definition does not end with a semicolon, but most Java statements do.

- In most cases (i.e., there are exceptions), the name of the class has to match the name of the file it is in, so this class has to be in a file named

HelloWorld.java. - There is no need for the HelloWorld code to have something like

#include <iostream>. The library files needed by the HelloWorld code is available by default without having to "include" them explicitly. - There is no need to

return 0at the end of the main method to indicate the execution was successful. It is considered as a successful execution unless an error is signalled specifically.

Can compile a simple Java program

To compile the HelloWorld program, open a command console, navigate to the folder containing the file, and run the following command.

>_ javac HelloWorld.java

If the compilation is successful, you should see a file HelloWorld.class. That file contains the byte code for your program. If the compilation is unsuccessful, you will be notified of the compile-time errors.

Notes:

javacis the java compiler that you get when you install the JDK.- For the above command to work, your console program should be able to find the javac executable (e.g., In Windows, the location of the

javac.exeshould be in thePATHsystem variable).

This page shows how to set PATH in different OS'es.

Can run a simple Java program

To run the HelloWorld program, in a command console, run the following command from the folder containing HelloWorld.class file.

>_ java HelloWorld

Notes:

javain the command above refers to the Java interpreter installed in your computer.- Similar to

javac, your console should be able to find the java executable.

When you run a Java program, you can encounter a . These errors are also called "exceptions" because they usually indicate that something exceptional (and bad) has happened. When a run-time error occurs, the interpreter displays an error message that explains what happened and where.

For example, modify the HelloWorld code to include the following line, compile it again, and run it.

System.out.println(5/0);

You should get a message like this:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArithmeticException: / by zero

at Hello.main(Hello.java:5)

Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) can automate the intermediate step of compiling. They usually have a Run button which compiles the code first and then runs it.

Example IDEs:

- IntelliJ IDEA

- Eclipse

- NetBeans

Exercises:

A. Install Java in your computer, if you haven't done so already. Java 17 is recommended.

Java installation guides for Windows/Mac/Linux can be found in this se-edu/guide.

Ensure the installation is correct, as follows.

- Open a command prompt.

- Run the command

java -version. Confirm that the output indicates that you have Java 17. Sample output:C:\Users\john>java -version java version "17._._" ... ... ... - Run the command

javacand ensure it results in a help message. If it outputs an error message such asjavac is not recognized as internal or external command, you need to configure thePATHvariable of your OS so that the OS know where yourjavacexecutable is.

B. Write, compile and run a small Java program (e.g., a HelloWorld program) in your computer. You can use any code editor to write the program but use the command prompt to compile and run the program. Here are suggested steps:

- Open notepad (or any other text editor)

- Copy paste this code into the editor.

public class HelloWorld { public static void main(String[] args) { System.out.println("Hello, World!"); } } - Save the file in an empty folder as

HelloWorld.java(ensure there the case match exactly and there is no.txtat the end). - Open a command prompt, and navigate to the folder where you saved the file.

c:> cd my-java-code c:\my-java-code> - Run the command

javac HelloWorld.java. Ensure there are no compile errors. Note how a file calledHelloWorld.classhas been created in that folder.c:\my-java-code>javac HelloWorld.java - Run the command

java HelloWorld(no.javaat the end). The output should beHello, World!.c:\my-java-code>java HelloWorld Hello, World!

C. Modify the code to print something else, save, compile, and run the program again.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Now that you know how to write the simplest of Java programs, you can move onto learning about basic language concepts, starting with data types.

At the end of the next section, there is an exercise ([Key Exercise] ByeWorld) that you need to submit on Coursemology. From this point onwards, programming exercises marked as [Key Exercise] need to be submitted on Coursemology.

Can use primitive data types

Java has a number of primitive data types, as given below:

byte: an integer in the range -128 to 127 (inclusive).short: an integer in the range -32,768 to 32,767 (inclusive).int: an integer in the range -231 to 231-1.long: An integer in the range -263 to 263-1.float: a single-precision 32-bit IEEE 754 floating point. This data type should never be used for precise values, such as currency. For that, you will need to use the java.math.BigDecimal class instead.double: a double-precision 64-bit IEEE 754 floating point. For decimal values, this data type is generally the default choice. This data type should never be used for precise values, such as currency.boolean: has only two possible values:trueandfalse.char: The char data type is a single 16-bit Unicode character. It has a minimum value of'\u0000'(or0) and a maximum value of'\uffff'(or65,535inclusive).

The String type (a peek)

Java has a built-in type called String to represent strings. While String is not a primitive type, strings are used often. String values are demarcated by enclosing in a pair of double quotes (e.g., "Hello"). You can use the + operator to concatenate strings (e.g., "Hello " + "!").

You’ll learn more about strings in a later section.

Resources:

- Oracle's tutorial on primitive data types

- A tutorial on primitive data types by beginnersbook.com

Can use variables

Java is a statically-typed language in that variables have a fixed type. Here are some examples of declaring variables and assigning values to them.

int x;

x = 5;

int hour = 11;

boolean isCorrect = true;

char capitalC = 'C';

byte b = 100;

short s = 10000;

int i = 100000;

You can use any name starting with a letter, underscore, or $ as a variable name but you cannot use Java keywords as variables names.

You can display the value of a variable using System.out.print or System.out.println (the latter goes to the next line after printing). To output multiple values on the same line, it’s common to use several print statements followed by println at the end.

int hour = 11;

int minute = 59;

System.out.print("The current time is ");

System.out.print(hour);

System.out.print(":");

System.out.print(minute);

System.out.println("."); //use println here to complete the line

System.out.println("done");

The current time is 11:59.

done

Use the keyword final to indicate that the variable value, once assigned, should not be allowed to change later i.e., act like a ‘constant’. By convention, names for constants are all uppercase, with the underscore character (_) between words.

final double CM_PER_INCH = 2.54;

Can use operators

Java supports the usual arithmetic operators, given below.

| Operator | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

+ | Additive operator | 2 + 3 5 |

- | Subtraction operator | 4 - 1 3 |

* | Multiplication operator | 2 * 3 6 |

/ | Division operator | 5 / 2 2 but 5.0 / 2 2.5 |

% | Remainder operator | 5 % 2 1 |

The following program uses some operators as part of an expression hour * 60 + minute:

int hour = 11;

int minute = 59;

System.out.print("Number of minutes since midnight: ");

System.out.println(hour * 60 + minute);

Number of minutes since midnight: 719

When an expression has multiple operators, normal operator precedence rules apply. Furthermore, you can use parentheses to specify a precise precedence.

Examples:

4 * 5 - 119(*has higher precedence than-)4 * (5 - 1)16(parentheses()have higher precedence than*)

Java does not allow .

The unary operators require only one operand; they perform various operations such as incrementing/decrementing a value by one, negating an expression, or inverting the value of a boolean.-- Java Tutorial

| Operator | Description -- Java Tutorial | example |

|---|---|---|

+ | Unary plus operator; indicates positive value (numbers are positive without this, however) | x = 5; y = +x y is 5 |

- | Unary minus operator; negates an expression | x = 5; y = -x y is -5 |

++ | Increment operator; increments a value by 1 | i = 5; i++ i is 6 |

-- | Decrement operator; decrements a value by 1 | i = 5; i-- i is 4 |

! | Logical complement operator; inverts the value of a boolean | foo = true; bar = !foo bar is false |

Relational operators are used to check conditions like whether two values are equal, or whether one is greater than the other. The following expressions show how they are used:

| Operator | Description | example true | example false |

|---|---|---|---|

x == y | x is equal to y | 5 == 5 | 5 == 6 |

x != y | x is not equal to y | 5 != 6 | 5 != 5 |

x > y | x is greater than y | 7 > 6 | 5 > 6 |

x < y | x is less than y | 5 < 6 | 7 < 6 |

x >= y | x is greater than or equal to y | 5 >= 5 | 4 >= 5 |

x <= y | x is less than or equal to y | 4 <= 5 | 6 <= 5 |

The result of a relational operator is a boolean value.

Java has three conditional operators that are used to operate on boolean values.

| Operator | Description | example true | example false |

|---|---|---|---|

&& | and | true && true true | true && false false |

|| | or | true || false true | false || false false |

! | not | not false | not true |

Resources:

- Oracle's tutorial on operators: part 1, part 2

- A tutorial on operators by tutorialspoint.com

Can use arrays

Arrays are indicated using square brackets ([]). To create the array itself, you have to use the new operator. Here are some example array declarations:

int[] counts;

counts = new int[4]; // create an int array of size 4

int size = 5;

double[] values;

values = new double[size]; //use a variable for the size

double[] prices = new double[size]; // declare and create at the same time

Alternatively, you can use the shortcut syntax to create and initialize an array:int[] values = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}; int[] anArray = { 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000 };-- Java Tutorial

The [] operator selects elements from an array. Array elements .

int[] counts = new int[4];

System.out.println("The first element is " + counts[0]);

counts[0] = 7; // set the element at index 0 to be 7

counts[1] = counts[0] * 2;

counts[2]++; // increment value at index 2

A Java array is aware of its size. A Java array prevents a programmer from indexing the array out of bounds. If the index is negative or not present in the array, the result is an error named ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException.

int[] scores = new int[4];

System.out.println(scores.length) // prints 4

scores[5] = 0; // causes an exception

4

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: 5

at Main.main(Main.java:6)

It is also possible to create arrays of more than one dimension:

String[][] names = { {"Mr. ", "Mrs. ", "Ms. "}, {"Smith", "Jones"} }; System.out.println(names[0][0] + names[1][0]); // Mr. Smith System.out.println(names[0][2] + names[1][1]); // Ms. Jones-- Java Tutorial

Passing arguments to a program

The args parameter of the main method is an array of Strings containing command line arguments supplied (if any) when running the program.

public class Foo{

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(args[0]);

}

}

You can run this program (after compiling it first) from the command line by typing:

>_ java Foo abc

abc

Resources:

- Oracle's tutorial on Arrays

- A tutorial on Arrays by tutorialspoint.com

- A video tutorial on Arrays by thenewboston

Exercises:

Write a Java program that takes two command line arguments and prints true or false to indicate if the two arguments have the same value. Follow the sample output given below.

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// add your code here

}

}

>_ java Main adam eve

Words given: adam, eve

They are the same: false

>_ java Main eve eve

Words given: eve, eve

They are the same: true

Use the following technique to compare two Strings(i.e., don't use ==). Reason: to be covered in a later topic.

String x = "foo";

boolean isSame = x.equals("bar") // false

isSame = x.equals("foo") // true

Hint

partial solution

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next up is learning how to control the flow of a Java program.

Can use branching

if-else statements

Java supports the usual forms of if statements:

if (x > 0) {

System.out.println("x is positive");

}

if (x % 2 == 0) {

System.out.println("x is even");

} else {

System.out.println("x is odd");

}

if (x > 0) {

System.out.println("x is positive");

} else if (x < 0) {

System.out.println("x is negative");

} else {

System.out.println("x is zero");

}

if (x == 0) {

System.out.println("x is zero");

} else {

if (x > 0) {

System.out.println("x is positive");

} else {

System.out.println("x is negative");

}

}

The braces are optional (but recommended) for branches that have only one statement. So we could have written the previous example this way ( Bad):

if (x % 2 == 0)

System.out.println("x is even");

else

System.out.println("x is odd");

switch statements

The switch statement can have a number of possible execution paths. A switch works with the byte, short, char, and int primitive data types. It also works with enums, String.

Here is an example (adapted from -- Java Tutorial):

public class SwitchDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int month = 8;

String monthString;

switch (month) {

case 1: monthString = "January";

break;

case 2: monthString = "February";

break;

case 3: monthString = "March";

break;

case 4: monthString = "April";

break;

case 5: monthString = "May";

break;

case 6: monthString = "June";

break;

case 7: monthString = "July";

break;

case 8: monthString = "August";

break;

case 9: monthString = "September";

break;

case 10: monthString = "October";

break;

case 11: monthString = "November";

break;

case 12: monthString = "December";

break;

default: monthString = "Invalid month";

break;

}

System.out.println(monthString);

}

}

August

Exercises:

Greeter

Write a Java program that takes a letter grade e.g., A+ as a command line argument and prints the CAP (aka GPA) value for that grade.

Use a switch statement in your code.

| A+ | A | A- | B+ | B | B- | C | Else |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0 |

Follow the sample output given below.

>_ java GradeHelper B CAP for grade B is 3.5

You can assume that the input is always in the correct format i.e., no need to handle invalid input cases.

Hint

Can use methods

Defining methods

Here’s an example of adding more methods to a class:

public class PrintTwice {

public static void printTwice(String s) {

System.out.println(s);

System.out.println(s);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

String sentence = “Polly likes crackers”

printTwice(sentence);

}

}

Polly likes crackers

Polly likes crackers

By convention, method names should be named in the camelCase format.

Similar to the main method, the printTwice method is public (i.e., it can be invoked from other classes) static and void.

Parameters

A method can specify parameters. The printTwice method above specifies a parameter of String type. The main method passes the argument "Polly likes crackers" to that parameter.

The value provided as an argument must have the same type as the parameter. Sometimes Java can convert an argument from one type to another automatically. For example, if the method requires a double, you can invoke it with an int argument 5 and Java will automatically convert the argument to the equivalent value of type double 5.0.

Because a variable declared inside a method only exists inside that method, such variables are called local variables. That applies to parameters of a method too. For example, In the code above, s cannot be used inside main because it is a parameter of the printTwice method and can only be used inside that method. If you try to use s inside main, you’ll get a compiler error. Similarly, inside printTwice there is no such thing as sentence. That variable belongs to main.

return statements

The return statement allows you to terminate a method before you reach the end of it:

public static void printLogarithm(double x) {

if (x <= 0.0) {

System.out.println("Error: x must be positive.");

return;

}

double result = Math.log(x);

System.out.println("The log of x is " + result);

}

It can be used to return a value from a method too:

public class AreaCalculator{

public static double calculateArea(double radius) {

double result = 3.14 * radius * radius;

return result;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

double area = calculateArea(12.5);

System.out.println(area);

}

}

Overloading

Java methods can be overloaded. If two methods do the same thing, it is natural to give them the same name. Having more than one method with the same name is called overloading, and it is legal in Java as long as each version has a different method signature (the signature of the method is the method name and ordered list of parameter types) . For example, the following overloading of the method calculateArea is allowed because the method signatures are different (i.e., calculateArea(double) vs calculateArea(double, double)).

public static double calculateArea(double radius) {

//...

}

public static double calculateArea(double height, double width) {

//...

}

Recursion

Methods can be recursive. Here is an example in which the nLines method calls itself recursively:

public static void nLines(int n) {

if (n > 0) {

System.out.println();

nLines(n - 1);

}

}

Resources:

- Oracle's tutorials on [methods][parameters]

- Method Overloading in Java a tutorial from javapoint.com. Also mentions the topic of a related topic type promotion.

Exercises:

Add the following method to the class given below.

public static double getGradeCap(String grade): Returns the CAP (aka GPA) value of the givengrade. The mapping from grades to CAP is given below.

| A+ | A | A- | B+ | B | B- | C | Else |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0 |

Do not change the code of the main method!

public class Main {

// ADD YOUR CODE HERE

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("A+: " + getGradeCap("A+"));

System.out.println("B : " + getGradeCap("B"));

}

}

A+: 5.0

B : 3.5

Hint

Can use loops

Java has while and for constructs for looping.

while loops

Here is an example while loop:

public static void countdown(int n) {

while (n > 0) {

System.out.println(n);

n = n - 1;

}

System.out.println("Blastoff!");

}

for loops

for loops have the form:

for (initializer; condition; update) {

statement(s);

}

Here is an example:

public static void printTable(int rows) {

for (int i = 1; i <= rows; i = i + 1) {

printRow(i, rows);

}

}

do-while loops

The while and for statements are pretest loops; that is, they test the condition first and at the beginning of each pass through the loop. Java also provides a posttest loop: the do-while statement. This type of loop is useful when you need to run the body of the loop at least once.

Here is an example (from -- Java Tutorial):

class DoWhileDemo {

public static void main(String[] args){

int count = 1;

do {

System.out.println("Count is: " + count);

count++;

} while (count < 11);

}

}

break and continue

A break statement exits the current loop.

Here is an example (from -- Java Tutorial):

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = new int[] { 1, 2, 3, 0, 4, 5, 0 };

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

if (numbers[i] == 0) {

break;

}

System.out.print(numbers[i]);

}

}

}

123

[Try the above code on Repl.it]

A continue statement skips the remainder of the current iteration and moves to the next iteration of the loop.

Here is an example (from -- Java Tutorial):

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = new int[] { 1, 2, 3, 0, 4, 5, 0 };

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

if (numbers[i] == 0) {

continue;

}

System.out.print(numbers[i]);

}

}

12345

Enhanced for loops

Since traversing arrays is so common, Java provides an alternative for-loop syntax that makes the code more compact. For example, consider a for loop that displays the elements of an array on separate lines:

for (int i = 0; i < values.length; i++) {

int value = values[i];

System.out.println(value);

}

We could rewrite the loop like this:

for (int value : values) {

System.out.println(value);

}

This statement is called an enhanced for loop. You can read it as, “for each value in values”.

Notice how the single line for (int value : values) replaces the first two lines of the standard for loop.

Exercises:

Add the following method to the class given below.

public static double[] getMultipleGradeCaps(String[] grades): Returns the CAP (aka GPA) values of the givengrades. e.g., if the input was the array["A+", "B"], the method returns[5.0, 3.5]. The mapping from grades to CAP is given below.

| A+ | A | A- | B+ | B | B- | C | Else |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0 |

Do not change the code of the main method!

public class Main {

// ADD YOUR CODE HERE

public static double getGradeCap(String grade) {

double cap = 0;

switch (grade) {

case "A+":

case "A":

cap = 5.0;

break;

case "A-":

cap = 4.5;

break;

case "B+":

cap = 4.0;

break;

case "B":

cap = 3.5;

break;

case "B-":

cap = 3.0;

break;

case "C":

cap = 2.5;

break;

default:

}

return cap;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] grades = new String[]{"A+", "A", "A-"};

double[] caps = getMultipleGradeCaps(grades);

for (int i = 0; i < grades.length; i++) {

System.out.println(grades[i] + ":" + caps[i]);

}

}

}

A+:5.0

A:5.0

A-:4.5

Hint

Guidance for the item(s) below:

🤔 In case you are puzzled by the sudden change of topic, it's because we take an iterative approach to covering topics, as explained in the panel below:

Guidance for the item(s) below:

First, let's learn a bit about tracking the change history of a project in general, at a higher level.

Can explain revision control

Given below is a general introduction to revision control, adapted from bryan-mercurial-guide:

Revision control is the process of managing multiple versions of a piece of information. In its simplest form, this is something that many people do by hand: every time you modify a file, save it under a new name that contains a number, each one higher than the number of the preceding version.

Manually managing multiple versions of even a single file is an error-prone task, though, so software tools to help automate this process have long been available. The earliest automated revision control tools were intended to help a single user to manage revisions of a single file. Over the past few decades, the scope of revision control tools has expanded greatly; they now manage multiple files, and help multiple people to work together. The best modern revision control tools have no problem coping with thousands of people working together on projects that consist of hundreds of thousands of files.

There are a number of reasons why you or your team might want to use an automated revision control tool for a project.

- It will track the history and evolution of your project, so you don't have to. For every change, you'll have a log of who made it; why they made it; when they made it; and what the change was.

- It makes it easier for you to collaborate when you're working with other people. For example, when people more or less simultaneously make potentially incompatible changes, the software will help you to identify and resolve those conflicts.

- It can help you to recover from mistakes. If you make a change that later turns out to be an error, you can revert to an earlier version of one or more files. In fact, a really good revision control tool will even help you to efficiently figure out exactly when a problem was introduced.

- It will help you to work simultaneously on, and manage the drift between, multiple versions of your project.

Most of these reasons are equally valid, at least in theory, whether you're working on a project by yourself, or with a hundred other people.

Revision: A revision (some seem to use it interchangeably with version while others seem to distinguish the two -- here, let us treat them as the same, for simplicity) is a state of a piece of information at a specific time that is a result of some changes to it e.g., if you modify the code and save the file, you have a new revision (or a new version) of that file.

RCS: Revision control software are the software tools that automate the process of Revision Control i.e. managing revisions of software artifacts.

Revision control software are also known as Version Control Software (VCS), and by a few other names.

Git is the most widely used RCS today. Other RCS tools include Mercurial, Subversion (SVN), Perforce, CVS (Concurrent Versions System), Bazaar, TFS (Team Foundation Server), and Clearcase.

Github is a web-based project hosting platform for projects using Git for revision control. Other similar services include GitLab, BitBucket, and SourceForge.

Can explain repositories

The repository is the database that stores the revision history. Suppose you want to apply revision control on files in a directory called ProjectFoo. In that case, you need to set up a repo (short for repository) in the ProjectFoo directory, which is referred to as the working directory of the repo. For example, Git uses a hidden folder named .git inside the working directory, to store the database of the working directory's revision history.

Repository (repo for short): The database of the history of a directory being tracked by an RCS software (e.g. Git).

Working directory: the root directory revision-controlled by Git (e.g., the directory in which the repo was initialized).

You can have multiple repos in your computer, each repo revision-controlling files of a different working directory, for examples, files of different projects.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Now that we know what RCS is in general, we can try to practice it ourselves using a specific tool i.e., Git.

The following section gives a specific scenario that includes the steps of initializing a Git repository.

If you are new to Git, you are highly recommended to follow those steps in your own computer to get some hands-on practice as you learn Git usage.

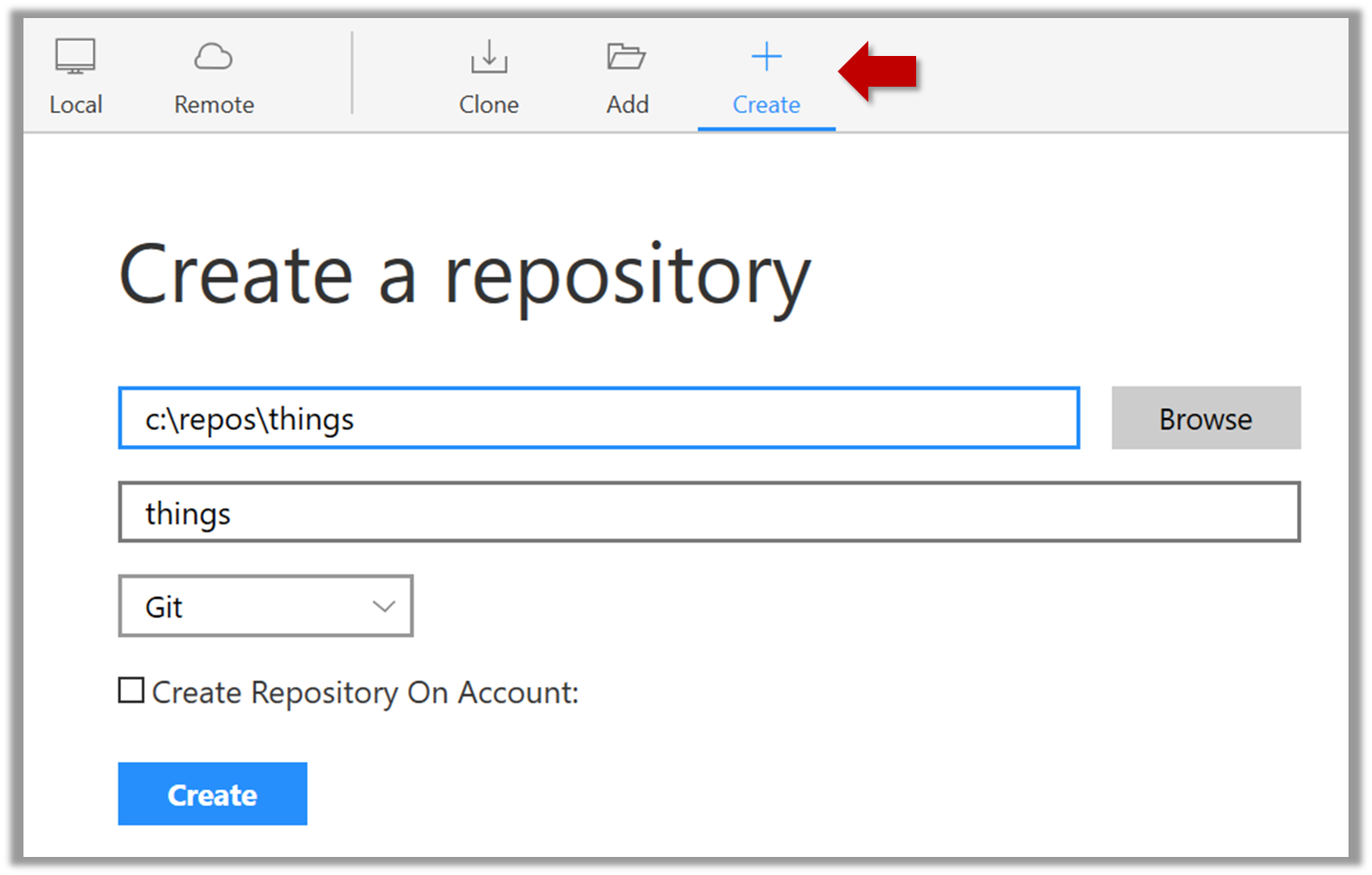

Can create a local Git repo

Let's take your first few steps in your Git journey.

0. Take a peek at the full picture(?). Optionally, if you are the sort who prefers to have some sense of the full picture before you get into the nitty-gritty details, watch the video in the panel below:

Git Overview

1. First, install Sourcetree (installation instructions), which is Git + a GUI for Git. If you prefer to use Git via the command line (i.e., without a GUI), you can install Git instead.

2. Next, create a directory for the repo (e.g., a directory named things).

3. Then, initialize a repository in that directory.

-

Windows: Click

File→Clone/New…→ Click on+ Createbutton on the top menu bar.

Enter the location of the directory and clickCreate. -

Mac:

New...→Create Local Repository(orCreate New Repository) → Click...button to select the folder location for the repository → click theCreatebutton.

Go to the things folder and observe how a hidden folder .git has been created.

Windows: To see the hidden folders, you might have to configure Windows Explorer to show hidden files first.

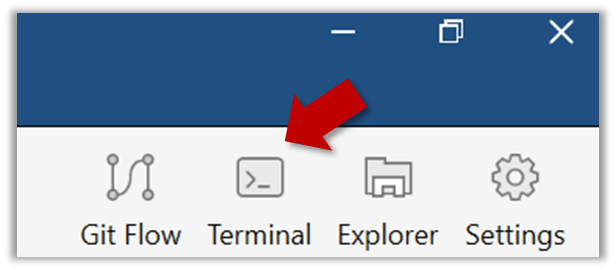

Open a Git Bash Terminal.

If you installed Sourcetree, you can click the Terminal button to open a GitBash terminal (on a Linux/Mac environment, even a regular terminal should do).

Navigate to the things directory.

Use the command git init which should initialize the repo.

$ cd /c/repos/things

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in c:/repos/things/.git/

You can use the list all command ls -a to view all files, which should show the .git directory that was created by the previous command.

$ ls -a

. .. .git

You can also use the git status command to check the status of the newly-created repo. It should respond with something like the following:

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# No commits yet

#

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

As you see above, this textbook explains how to use Git via Sourcetree (a GUI client) as well as via the Git CLI. If you are new to Git, we recommend you learn both the GUI method and the CLI method -- The GUI method will help you visualize the result better while the CLI method is more universal (i.e., you will not be tied to any GUI) and more flexible/powerful.

It is fine to learn the CLI way only (using Sourcetree is optional), especially if you normally prefer to work with CLI over GUI.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

For the next few sections, the drill is the same: first learn the high-level explanation of a revision control concept, and then follow the given scenarios yourself to learn how to apply that concept using Git.

Can explain saving history

Tracking and ignoring

In a repo, you can specify which files to track and which files to ignore. For example, we can configure Git to ignore temporary files created during the build/test process, as it does not make sense to track their version history.

Staging and committing

Committing saves a snapshot of the current state of the tracked files in the revision control history. Such a snapshot is also called a commit (i.e. the noun).

Commit (noun): a change (aka a revision) saved in the Git revision history.

(verb): the act of creating a commit i.e., saving a change in the working directory into the Git revision history.

When ready to commit, you first add the specific changes you want to commit to a staging area. This intermediate step allows you to commit only some changes while saving other changes for a later commit.

Stage (verb): Instructing Git to prepare a file for committing.

Can commit using Git

After initializing a repository, Git can help you with revision controlling files inside the working directory. However, it is not automatic. You need to tell Git which of your changes (aka revisions) should be committed to its memory for later use. Saving changes into Git's memory in that way is called committing and a change saved to the revision history is called a commit.

Here are the steps you can follow to learn how to create Git commits:

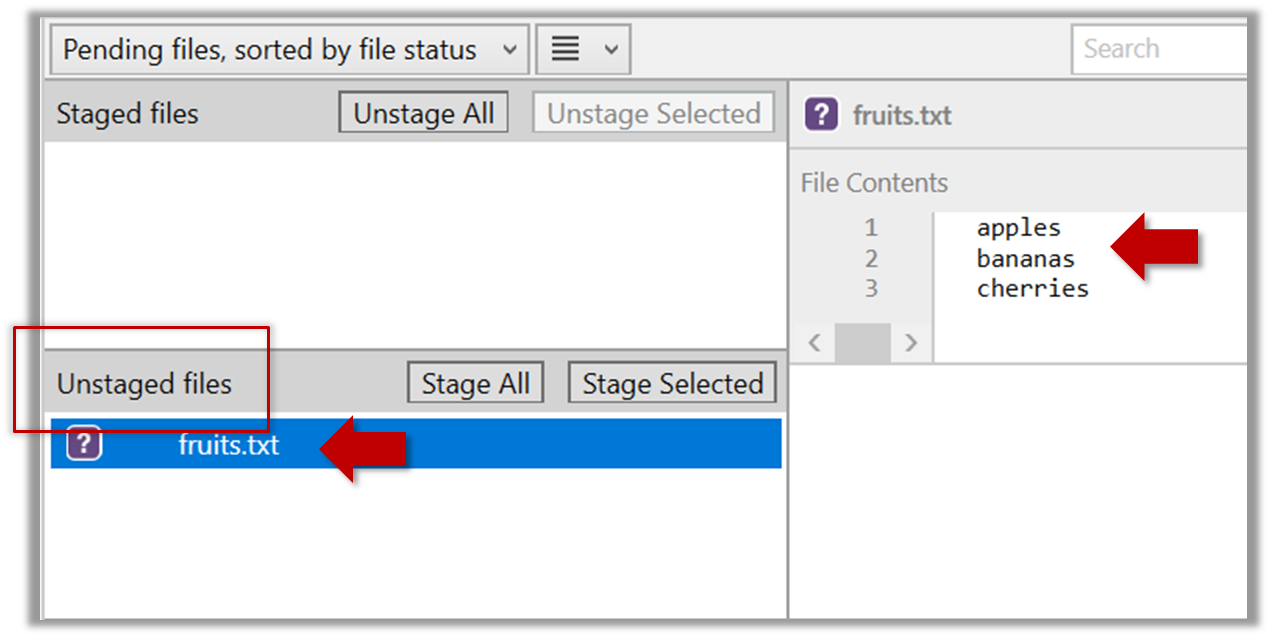

1. Do some changes to the content inside the working directory e.g., create a file named fruits.txt in the things directory and add some dummy text to it.

2. Observe how the file is detected by Git.

The file is shown as ‘unstaged’.

You can use the git status command to check the status of the working directory.

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# No commits yet

#

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# a.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

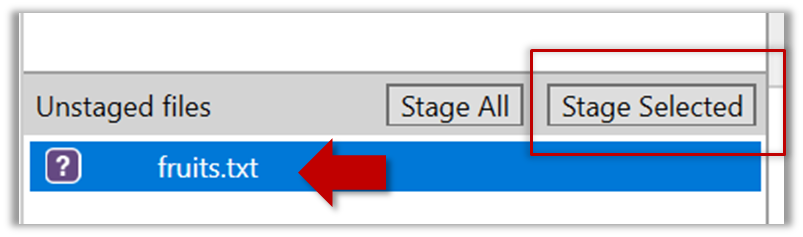

3. Stage the changes to commit: Although Git has detected the file in the working directory, it will not do anything with the file unless you tell it to. Suppose you want to commit the current changes to the file. First, you should stage the file, which is how you tell Git which changes you want to include in the next commit.

When you stage a change, the change is moved to the staging area, which is a file Git uses to store information about what will go into your next commit. The staging area is also called the 'index' by the Git practitioners.

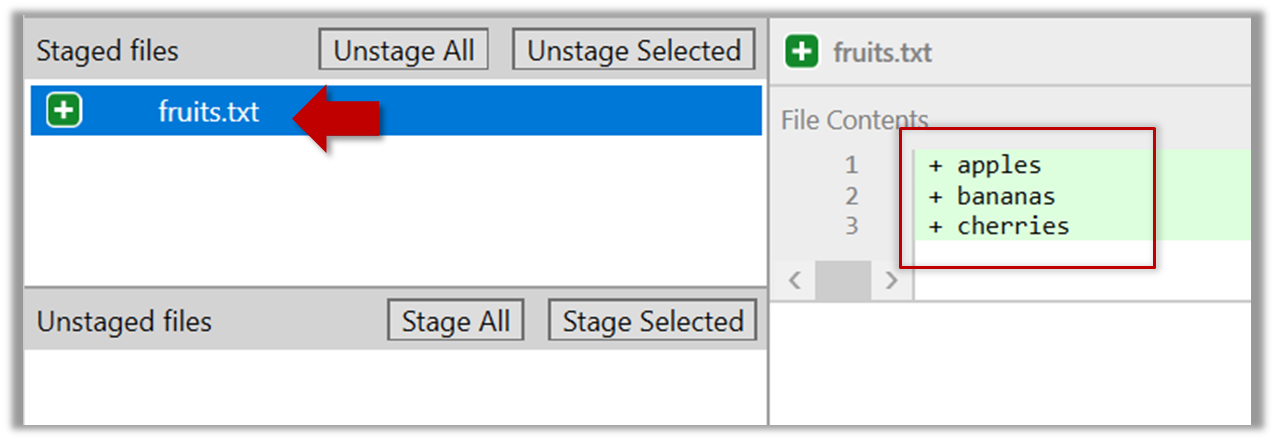

Select the fruits.txt and click on the Stage Selected button.

fruits.txt should appear in the Staged files panel now.

If Sourcetree shows a \ No newline at the end of the file message below the staged lines (i.e., below the cherries line in the above screenshot), that is because you did not hit enter after entering the last line of the file (hence, Git is not sure if that line is complete). To rectify, move the cursor to end of the last line in that file and hit enter (like you are adding a blank line below it). This new change will now appear as an 'unstaged' change. Stage it as well.

You can use the stage or the add command (they are synonyms, add is the more popular choice) to stage files.

$ git add fruits.txt

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# No commits yet

#

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

#

# new file: fruits.txt

#

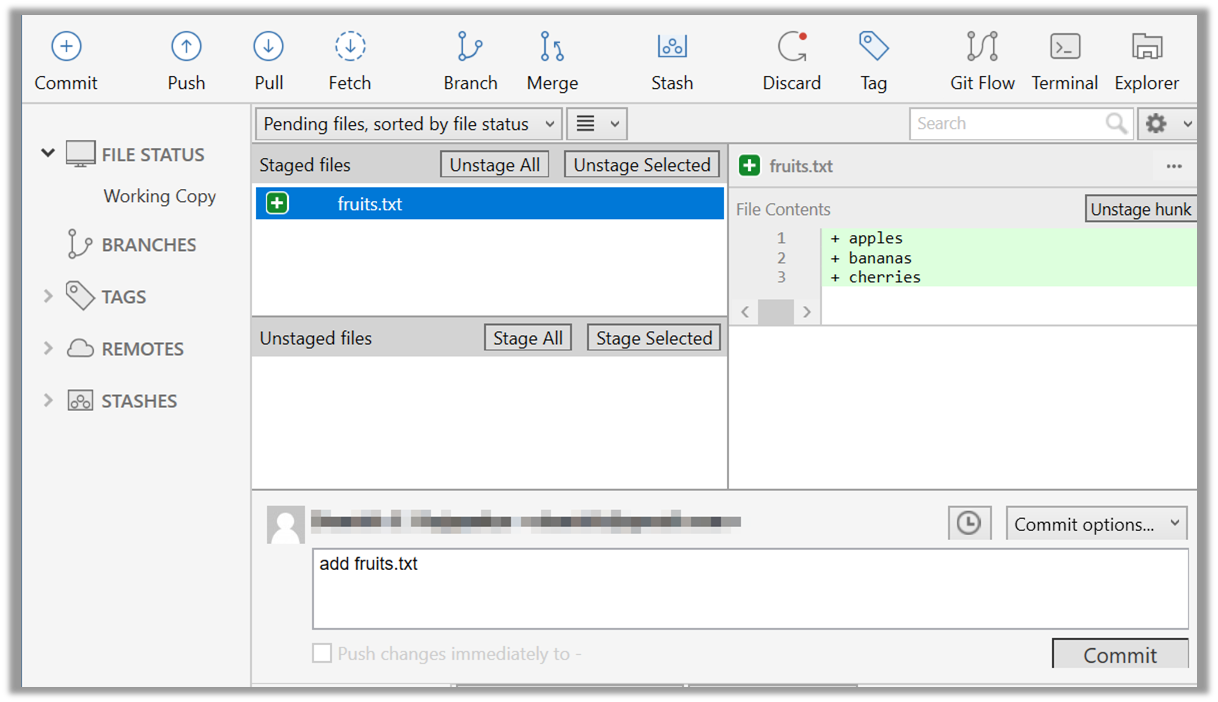

4. Commit the staged version of fruits.txt.

Click the Commit button, enter a commit message e.g. add fruits.txt into the text box, and click Commit.

Use the commit command to commit. The -m switch is used to specify the commit message.

$ git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

You can use the log command to see the commit history.

$ git log

commit 8fd30a6910efb28bb258cd01be93e481caeab846

Author: … < … @... >

Date: Wed Jul 5 16:06:28 2017 +0800

Add fruits.txt

Note the existence of something called the master branch. Git uses a mechanism called 'branches' to facilitate evolving file content in parallel (we'll learn git branching in a later topic). Furthermore, Git auto-creates a branch named master (or main) on which the commits go on by default.

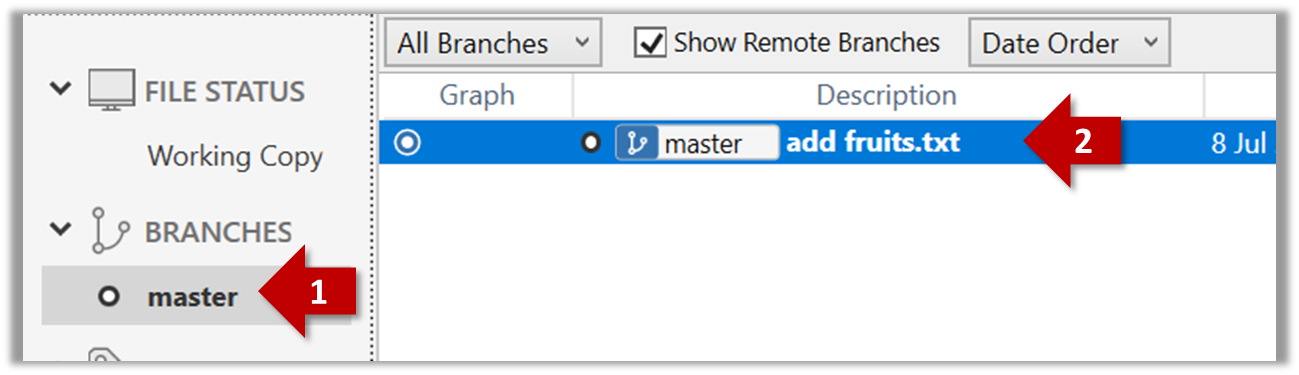

Expand the BRANCHES menu and click on the master to view the history graph, which contains only one node at the moment, representing the commit you just added. Also note a label master attached to the commit.

This label points to the latest commit on the master branch.

Run the git status command and note how the output contains the phrase on branch master.

5. Do a few more commits.

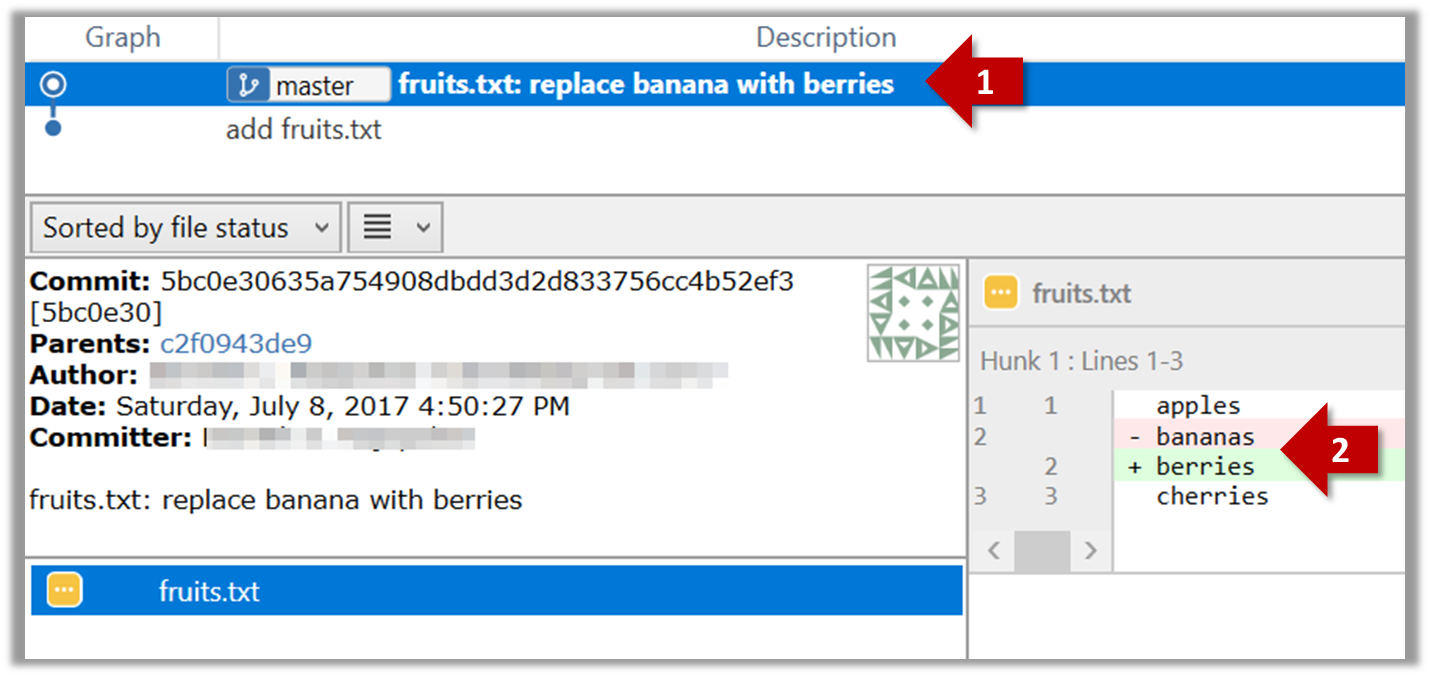

Make some changes to

fruits.txt(e.g. add some text and delete some text). Stage the changes, and commit the changes using the same steps you followed before. You should end up with something like this.

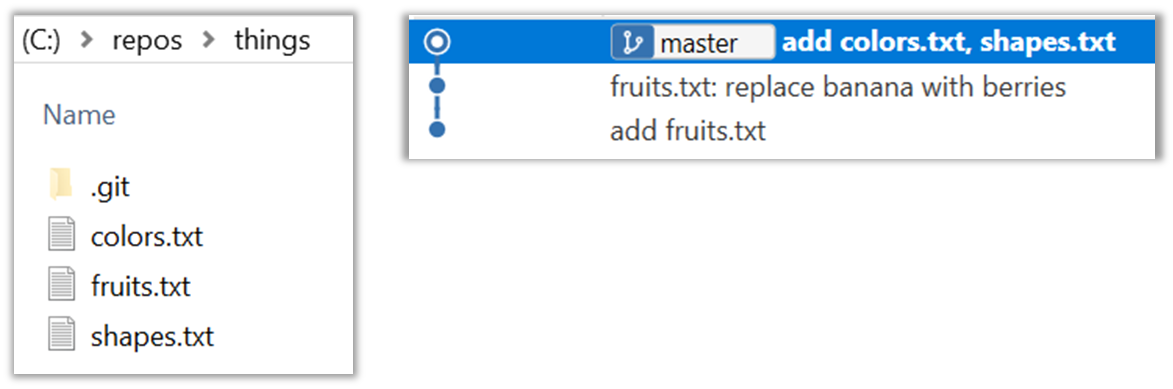

Next, add two more files

colors.txtandshapes.txtto the same working directory. Add a third commit to record the current state of the working directory.

You can decide what to stage and what to leave unstaged. When staging changes to commit, you can leave some files unstaged, if you wish to not include them in the next commit. In fact, Git even allows some changes in a file to be staged, while other changes in the same file to be unstaged. This flexibility is particularly useful when you want to put all related changes into a commit while leaving out unrelated changes.

6. See the revision graph: Note how commits form a path-like structure aka the revision tree/graph. In the revision graph, each commit is shown as linked to its 'parent' commit (i.e., the commit before it).

To see the revision graph, click on the History item (listed under the WORKSPACE section) on the menu on the right edge of Sourcetree.

The gitk command opens a rudimentary graphical view of the revision graph.

How to undo/delete a commit?

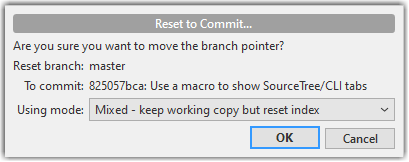

To undo the last commit, right-click on the commit just before it, and choose Reset current branch to this commit.

In the next dialog, choose the mode Mixed - keep working copy but reset index option. This will make the offending commit disappear but will keep the changes that you included in that commit intact.

If you use the Soft - ... mode instead, the last commit will be undone as before, but the changes included in that commit will stay in the staging area.

To delete the last commit entirely (i.e., undo the commit and also discard the changes included in that commit), do as above but choose the Hard - ... mode instead.

To undo/delete last n commits, right-click on the commit just before the last n commits, and do as above.

To undo the last commit, but keep the changes in the staging area, use the following command.

$ git reset --soft HEAD~1

To undo the last commit, and remove the changes from the staging area (but not discard the changes), used --mixed instead of --soft.

$ git reset --mixed HEAD~1

To delete the last commit entirely (i.e., undo the commit and also discard the changes included in that commit), do as above but use the --hard flag instead (i.e., do a hard reset).

$ git reset --hard HEAD~1

To undo/delete last n commits: HEAD~1 is used to tell Git you are targeting the commit one position before the latest commit -- in this case the target commit is the one we want to reset to, not the one we want to undo (as the command used is reset). To undo/delete two last commits, you can use HEAD~2, and so on.

Can set Git to ignore files

Often, there are files inside the Git working folder that you don't want to revision-control e.g., temporary log files. Follow the steps below to learn how to configure Git to ignore such files.

1. Add a file into your repo's working folder that you supposedly don't want to revision-control e.g., a file named temp.txt. Observe how Git has detected the new file.

2. Configure Git to ignore that file:

The file should be currently listed under Unstaged files. Right-click it and choose Ignore…. Choose Ignore exact filename(s) and click OK.

Observe that a file named .gitignore has been created in the working directory root and has the following line in it.

temp.txt

Create a file named .gitignore in the working directory root and add the following line in it.

temp.txt

The .gitignore file

The .gitignore file tells Git which files to ignore when tracking revision history. That file itself can be either revision controlled or ignored.

To version control it (the more common choice – which allows you to track how the

.gitignorefile changes over time), simply commit it as you would commit any other file.To ignore it, follow the same steps you followed above when you set Git to ignore the

temp.txtfile.It supports file patterns e.g., adding

temp/*.tmpto the.gitignorefile prevents Git from tracking any.tmpfiles in thetempdirectory.

More information about the .gitignore file: git-scm.com/docs/gitignore

Files recommended to be omitted from version control

- Binary files generated when building your project e.g.,

*.class,*.jar,*.exe(reasons: 1. no need to version control these files as they can be generated again from the source code 2. Revision control systems are optimized for tracking text-based files, not binary files. - Temporary files e.g., log files generated while testing the product

- Local files i.e., files specific to your own computer e.g., local settings of your IDE

- Sensitive content i.e., files containing sensitive/personal information e.g., credential files, personal identification data (especially, if there is a possibility of those files getting leaked via the revision control system).

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Having learned how to use Git in your own computer, let's also learn a bit about working with remote repositories too. While it seems like a bit 'too much' to take in one week, but we want you to start using Git in your iP (individual project) from the very beginning.

Can explain remote repositories

Remote repositories are repos that are hosted on remote computers and allow remote access. They are especially useful for sharing the revision history of a codebase among team members of a multi-person project. They can also serve as a remote backup of your codebase.

It is possible to set up your own remote repo on a server, but the easier option is to use a remote repo hosting service such as GitHub or BitBucket.

You can clone a repo to create a copy of that repo in another location on your computer. The copy will even have the revision history of the original repo i.e., identical to the original repo. For example, you can clone a remote repo onto your computer to create a local copy of the remote repo.

When you clone from a repo, the original repo is commonly referred to as the upstream repo. A repo can have multiple upstream repos. For example, let's say a repo repo1 was cloned as repo2 which was then cloned as repo3. In this case, repo1 and repo2 are upstream repos of repo3.

You can pull (or fetch) from one repo to another, to receive new commits in the second repo, but only if the repos have a shared history. Let's say some new commits were added to the after you cloned it, and you would like to copy over those new commits to your own clone i.e., sync your clone with the upstream repo. In that case, you can pull from the upstream repo to your clone.

You can push new commits in one repo to another repo which will copy the new commits onto the destination repo. Note that pushing to a repo requires you to have write-access to it. Furthermore, you can push between repos only if those repos have a shared history among them (i.e., one was created by copying the other at some point in the past).

Cloning, pushing, and pulling/fetching can be done between two local repos too, although it is more common for them to involve a remote repo.

A repo can work with any number of other repositories as long as they have a shared history e.g., repo1 can pull from (or push to) repo2 and repo3 if they have a shared history between them.

A fork is a remote copy of a remote repo. As you know, cloning creates a local copy of a repo. In contrast, forking creates a remote copy of a repo hosted on remote service such as GitHub. This is particularly useful if you want to play around with a GitHub repo, but you don't have write permissions to it; you can simply fork the repo and do whatever you want with the fork as you are the owner of the fork.

A pull request (PR for short) is a mechanism for contributing code to a remote repo i.e., "I'm requesting you to pull my proposed changes to your repo". It's feature provided by RCS platforms such as GitHub. For this to work, the two repos must have a shared history. The most common case is sending PRs from a fork to its repo.

Can clone a remote repo

Given below is an example scenario you can try yourself to learn Git cloning.

Suppose you want to clone the sample repo samplerepo-things to your computer.

Note that the URL of the GitHub project is different from the URL you need to clone a repo in that GitHub project. e.g.

GitHub project URL: https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-things

Git repo URL: https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-things.git (note the .git at the end)

File → Clone / New… and provide the URL of the repo and the destination directory.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you are likely to be using an IDE for the iP, let's learn at least enough about IDEs to get you started using one.

Can explain IDEs

Professional software engineers often write code using Integrated Development Environments (IDEs). IDEs support most development-related work within the same tool (hence, the term integrated).

An IDE generally consists of:

- A source code editor that includes features such as syntax coloring, auto-completion, easy code navigation, error highlighting, and code-snippet generation.

- A compiler and/or an interpreter (together with other build automation support) that facilitates the compilation/linking/running/deployment of a program.

- A debugger that allows the developer to execute the program one step at a time to observe the run-time behavior in order to locate bugs.

- Other tools that aid various aspects of coding e.g. support for automated testing, drag-and-drop construction of UI components, version management support, simulation of the target runtime platform, modeling support, AI-assisted coding help, collaborative coding with others.

Examples of popular IDEs:

- Java: Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, NetBeans

- C#, C++: Visual Studio

- Swift: XCode

- Python: PyCharm

- Multiple languages: VS Code

Some web-based IDEs have appeared in recent times too e.g., Amazon's Cloud9 IDE.

Some experienced developers, in particular those with a UNIX background, prefer lightweight yet powerful text editors with scripting capabilities (e.g. Emacs) over heavier IDEs.

Can navigate code effectively using IDE features

Some useful navigation shortcuts:

- Quickly locate a file by name.

- Go to the definition of a method from where it is used.

- Go back to the previous location.

- View the documentation of a method from where the method is being used, without navigating to the method itself.

- Find where a method/field is being used.

IntelliJ IDEA Code Navigation

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you know, one of the objectives of the iP is to raise the quality of your code. We'll be learning about various ways to improve the code quality in the next few weeks, starting with coding standards.

Can explain the importance of code quality

Always code as if the person who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live. -- Martin Golding

Production code needs to be of high quality. Given how the world is becoming increasingly dependent on software, poor quality code is something no one can afford to tolerate.

Can explain the need for following a standard

One essential way to improve code quality is to follow a consistent style. That is why software engineers usually follow a strict coding standard (aka style guide).

The aim of a coding standard is to make the entire codebase look like it was written by one person. A coding standard is usually specific to a programming language and specifies guidelines such as the locations of opening and closing braces, indentation styles and naming styles (e.g. whether to use Hungarian style, Pascal casing, Camel casing, etc.). It is important that the whole team/company uses the same coding standard and that the standard is generally not inconsistent with typical industry practices. If a company's coding standard is very different from what is typically used in the industry, new recruits will take longer to get used to the company's coding style.

IDEs can help to enforce some parts of a coding standard e.g. indentation rules.