A textual description (i.e. prose) can be used to describe requirements. Prose is especially useful when describing abstract ideas such as the vision of a product.

The product vision of the TEAMMATES Project given below is described using prose.

TEAMMATES aims to become the biggest student project in the world (biggest here refers to 'many contributors, many users, large codebase, evolving over a long period'). Furthermore, it aims to serve as a training tool for Software Engineering students who want to learn SE skills in the context of a non-trivial real software product.

Avoid using lengthy prose to describe requirements; they can be hard to follow.

Feature list: A list of features of a product grouped according to some criteria such as aspect, priority, order of delivery, etc.

A sample feature list from a simple Minesweeper game (only a brief description has been provided to save space):

- Basic play – Single player play.

- Difficulty levels

- Medium levels

- Advanced levels

- Versus play – Two players can play against each other.

- Timer – Additional fixed time restriction on the player.

- ...

User story: User stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the new capability, usually a user or customer of the system. [Mike Cohn]

A common format for writing user stories is:

User story format: As a {user type/role} I can {function} so that {benefit}

Examples (from a Learning Management System):

- As a student, I can download files uploaded by lecturers, so that I can get my own copy of the files

- As a lecturer, I can create discussion forums, so that students can discuss things online

- As a tutor, I can print attendance sheets, so that I can take attendance during the class

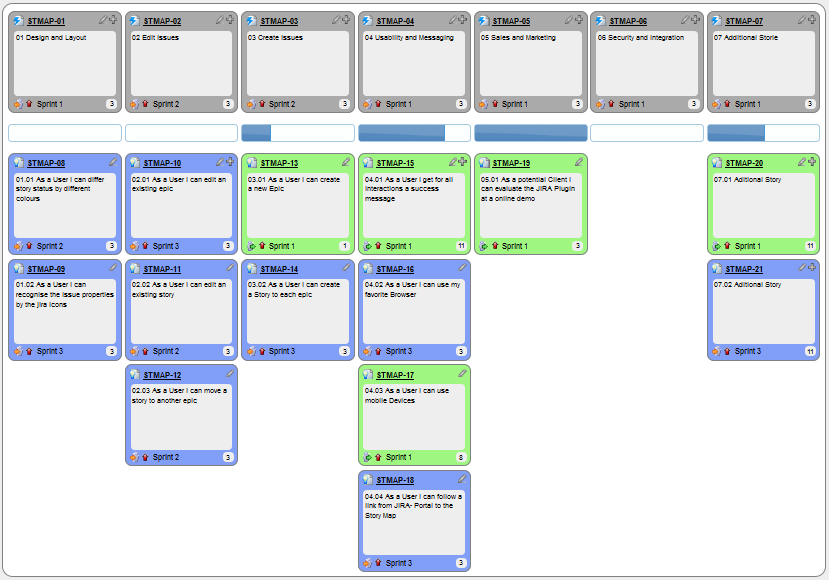

You can write user stories using a physical medium or a digital tool. For example, you can use index cards or sticky notes, and arrange them on walls or tables. Alternatively, you can use a software (e.g., GitHub Project Boards, Trello, Google Docs, ...) to manage user stories digitally.

User stories in use

With sticky notes

With paper

With software

The {benefit} can be omitted if it is obvious.

As a user, I can login to the system so that I can access my data

It is recommended to confirm there is a concrete benefit even if you omit it from the user story. If not, you could end up adding features that have no real benefit.

You can add more characteristics to the {user role} to provide more context to the user story.

- As a forgetful user, I can view a password hint, so that I can recall my password.

- As an expert user, I can tweak the underlying formatting tags of the document, so that I can format the document exactly as I need.

You can write user stories at various levels. High-level user stories, called epics (or themes) cover bigger functionality. You can then break down these epics to multiple user stories of normal size.

[Epic] As a lecturer, I can monitor student participation levels

- As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student

so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum - As a lecturer, I can view webcast view records of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not view webcasts - As a lecturer, I can view file download statistics of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not download lecture materials

You can add conditions of satisfaction to a user story to specify things that need to be true for the user story implementation to be accepted as ‘done’.

As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum.

Conditions:

Separate post count for each forum should be shown

Total post count of a student should be shown

The list should be sortable by student name and post count

Other useful info that can be added to a user story includes (but not limited to)

- Priority: how important the user story is

- Size: the estimated effort to implement the user story

- Urgency: how soon the feature is needed

User stories capture user requirements in a way that is convenient for , , and .

[User stories] strongly shift the focus from writing about features to discussing them. In fact, these discussions are more important than whatever text is written. [Mike Cohn, MountainGoat Software 🔗]

User stories differ from mainly in the level of detail. User stories should only provide enough details to make a reasonably low risk estimate of how long the user story will take to implement. When the time comes to implement the user story, the developers will meet with the customer face-to-face to work out a more detailed description of the requirements. [more...]

User stories can capture non-functional requirements too because even NFRs must benefit some stakeholder.

An example of an NFR captured as a user story:

| As a | I want to | so that |

|---|---|---|

| impatient user | to be able to experience reasonable response time from the website while up to 1000 concurrent users are using it | I can use the app even when the traffic is at the maximum expected level |

Given their lightweight nature, user stories are quite handy for recording requirements during early stages of requirements gathering.

A recipe for brainstorming user stories

Given below is a possible recipe you can take when using user stories for early stages of requirement gathering.

Step 0: Clear your mind of preconceived product ideas

Even if you already have some idea of what your product will look/behave like in the end, clear your mind of those ideas. The product is the solution. At this point, we are still at the stage of figuring out the problem (i.e., user requirements). Let's try to get from the problem to the solution in a systematic way, one step at a time.

Step 1: Define the target user as a persona:

Decide your target user's profile (e.g. a student, office worker, programmer, salesperson) and work patterns (e.g. Does he work in groups or alone? Does he share his computer with others?). A clear understanding of the target user will help when deciding the importance of a user story. You can even narrow it down to a persona. Here is an example:

Jean is a university student studying in a non-IT field. She interacts with a lot of people due to her involvement in university clubs/societies. ...

Step 2: Define the problem scope:

Decide the exact problem you are going to solve for the target user. It is also useful to specify what related problems it will not solve so that the exact scope is clear.

ProductX helps Jean keep track of all her school contacts. It does not cover communicating with contacts.

Step 3: List scenarios to form a narrative:

Think of the various scenarios your target user is likely to go through as she uses your app. Following a chronological sequence as if you are telling a story might be helpful.

A. First use:

- Jean gets to know about ProductX. She downloads it and launches it to check out what it can do.

- After playing around with the product for a bit, Jean wants to start using it for real.

- ...

B. Second use: (Jean is still a beginner)

- Jean launches ProductX. She wants to find ...

- ...

C. 10th use: (Jean is a little bit familiar with the app)

- ...

D. 100th use: (Jean is an expert user)

- Jean launches the app and does ... and ... followed by ... as per her usual habit.

- Jean feels some of the data in the app are no longer needed. She wants to get rid of them to reduce clutter.

More examples that might apply to some products:

- Jean uses the app at the start of the day to ...

- Jean uses the app before going to sleep to ...

- Jean hasn't used the app for a while because she was on a three-month training programme. She is now back at work and wants to resume her daily use of the app.

- Jean moves to another company. Some of her clients come with her but some don't.

- Jean starts freelancing in her spare time. She wants to keep her freelancing clients separate from her other clients.

Step 4: List the user stories to support the scenarios:

Based on the scenarios, decide on the user stories you need to support. For example, based on the scenario 'A. First use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As a potential user exploring the app, I can see the app populated with sample data, so that I can easily see how the app will look like when it is in use.

- As a user ready to start using the app, I can purge all current data, so that I can get rid of sample/experimental data I used for exploring the app.

To give another example, based on the scenario 'D. 100th use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As an expert user, I can create shortcuts for tasks, so that I can save time on frequently performed tasks.

- As a long-time user, I can archive/hide unused data, so that I am not distracted by irrelevant data.

Do not 'evaluate' the value of user stories while brainstorming. Reason: an important aspect of brainstorming is not judging the ideas generated.

Other tips:

- Don't be too hasty to discard 'unusual' user stories: Those might make your product unique and stand out from the rest, at least for the target users.

- Don't go into too much detail:

For example, consider this user story:

As a user, I want to see a list of tasks that need my attention most at the present time, so that I pay attention to them first.

When discussing this user story, don't worry about what tasks should be considered 'needs my attention most at the present time'. Those details can be worked out later. - Don't be biased by preconceived product ideas: When you are at the stage of identifying user needs, clear your mind of ideas you have about what your end product will look like. That is, don't try to reverse-engineer a preconceived product idea into user stories.

- Don't discuss implementation details or whether you are actually going to implement it: When gathering requirements, your decision is whether the user's need is important enough for you to want to fulfil it. Implementation details can be discussed later. If a user story turns out to be too difficult to implement later, you can always omit it from the implementation plan.

While use cases can be recorded on in the initial stages, an online tool is more suitable for longer-term management of user stories, especially if the team is not .

Tool Examples: How to use some example online tools to manage user stories

Resources:

- This article by Mike Cohn from MountainGoatSoftware explains how to use user stories to capture NFRs.

Use case: A description of a set of sequences of actions, including variants, that a system performs to yield an observable result of value to an actor [ 📖 : ].

A use case describes an interaction between the user and the system for a specific functionality of the system.

Example 1: 'transfer money' use case for an online banking system

System: Online Banking System (OBS) Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money Actor: User MSS: 1. User chooses to transfer money. 2. OBS requests for details of the transfer. 3. User enters the requested details. 4. OBS requests for confirmation. 5. User confirms. 6. OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance. Use case ends.

Extensions:

3a. OBS detects an error in the entered data.

3a1. OBS requests for the correct data.

3a2. User enters new data.

Steps 3a1-3a2 are repeated until the data entered are correct.

Use case resumes from step 4.

3b. User requests to effect the transfer in a future date.

3b1. OBS requests for confirmation.

3b2. User confirms future transfer.

Use case ends.

*a. At any time, User chooses to cancel the transfer.

*a1. OBS requests to confirm the cancellation.

*a2. User confirms the cancellation.

Use case ends.

Example 2: 'upload file' use case of an LMS

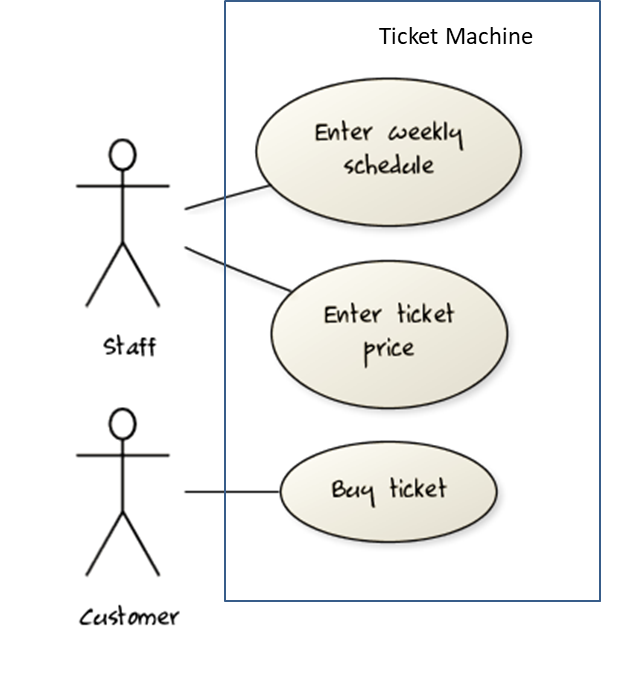

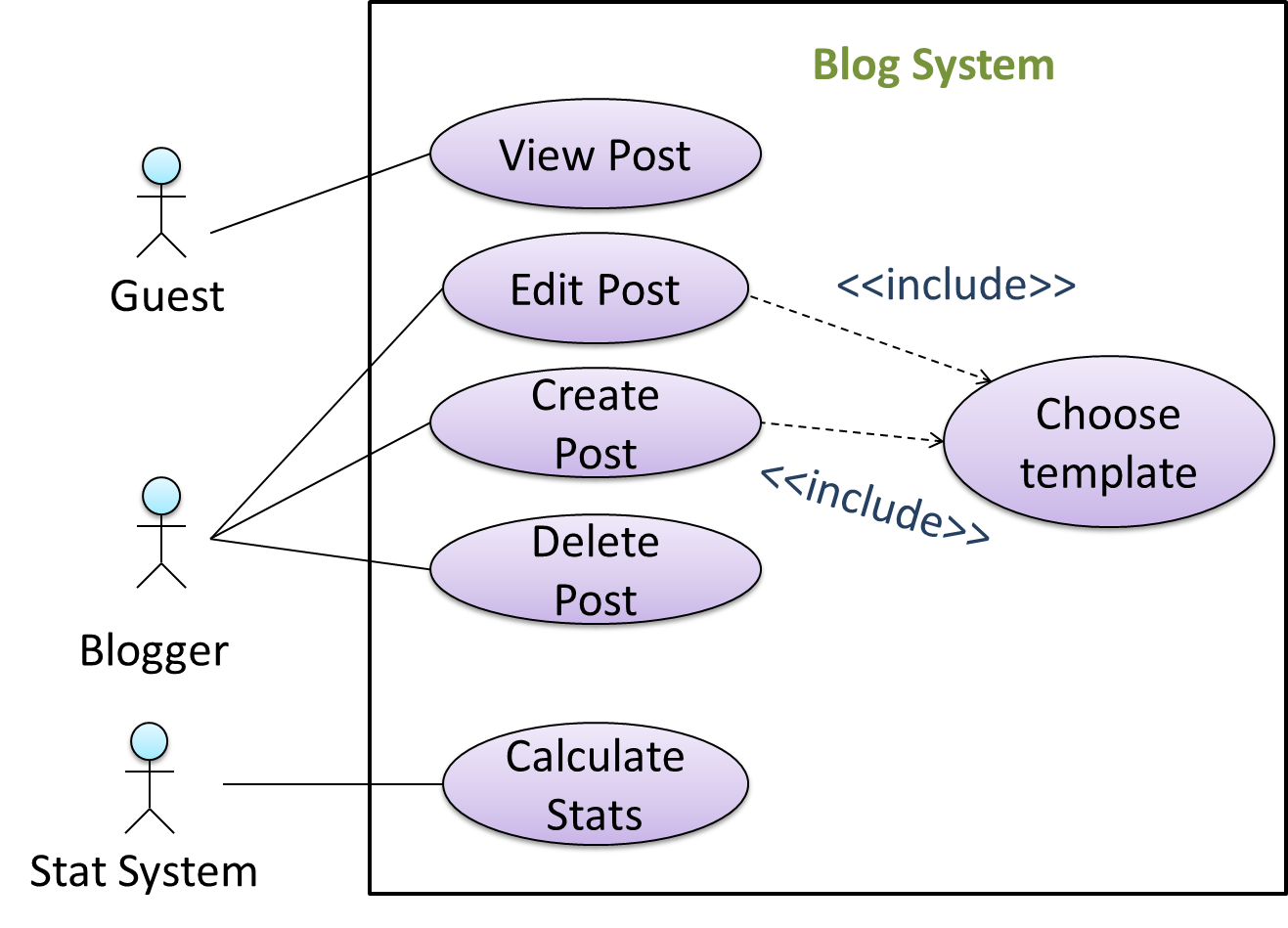

UML includes a diagram type called use case diagrams that can illustrate use cases of a system visually, providing a visual ‘table of contents’ of the use cases of a system.

In the example on the right, note how use cases are shown as ovals and user roles relevant to each use case are shown as stick figures connected to the corresponding ovals.

Use cases capture the functional requirements of a system.

A use case is an interaction between a system and its actors.

Actors in Use Cases

Actor: An actor (in a use case) is a role played by a user. An actor can be a human or another system. Actors are not part of the system; they reside outside the system.

Some example actors for a Learning Management System:

- Actors: Guest, Student, Staff, Admin, , .

A use case can involve multiple actors.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Use case: UC01 Conduct Survey

- Actors: Staff, Student

An actor can be involved in many use cases.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Actor: Staff

- Use cases: UC01 Conduct Survey, UC02 Set Up Course Schedule, UC03 Email Class, ...

A single person/system can play many roles.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Person: a student

- Actors (or Roles): Student, Guest, Tutor

Many persons/systems can play a single role.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Actor (or role): Student

- Persons that can play this role: undergraduate student, graduate student, a staff member doing a part-time course, exchange student

Use cases can be specified at various levels of detail.

Consider the three use cases given below. Clearly, (a) is at a higher level than (b) and (b) is at a higher level than (c).

- System: LearnSys

- Use cases:

a. Conduct a survey

b. Take the survey

c. Answer survey question

While modeling user-system interactions,

- start with high level use cases and progressively work toward lower level use cases.

- be mindful of which level of detail you are working at and not to mix use cases of different levels.

Writing use case steps

The main body of the use case is a sequence of steps that describes the interaction between the system and the actors. Each step is given as a simple statement describing who does what.

An example of the main body of a use case.

- Student requests to upload file

- LMS requests for the file location

- Student specifies the file location

- LMS uploads the file

A use case describes only the externally visible behavior, not internal details, of a system i.e. should minimize details that are not part of the interaction between the user and the system.

This example use case step refers to a behavior not externally visible (i.e., user is not meant to be aware of).

- LMS saves the file into the cache and indicates success.

A step gives the intention of the actor (not the mechanics). That means UI details are usually omitted. The idea is to leave as much flexibility to the UI designer as possible. That is, the use case specification should be as general as possible (less specific) about the UI.

The first example below is not a good use case step because it contains UI-specific details. The second one is better because it omits UI-specific details.

Bad : User right-clicks the text box and chooses ‘clear’

Good : User clears the input

A use case description can show loops too.

An example of how you can show a loop:

Software System: SquareGame

Use case: - Play a Game

Actors: Player (multiple players)

MSS:

- A Player starts the game.

- SquareGame asks for player names.

- Each Player enters his own name.

- SquareGame shows the order of play.

- SquareGame prompts for the current Player to throw a die.

- Current Player adjusts the throw speed.

- Current Player triggers the die throw.

- SquareGame shows the face value of the die.

- SquareGame moves the Player's piece accordingly.

Steps 5-9 are repeated for each Player, and for as many rounds as required until a Player reaches the 100th square. - SquareGame shows the Winner.

Use case ends.

The Main Success Scenario (MSS) describes the most straightforward interaction for a given use case, which assumes that nothing goes wrong. This is also called the Basic Course of Action or the Main Flow of Events of a use case.

Note how the MSS in the example below assumes that all entered details are correct and ignores problems such as timeouts, network outages etc. For example, the MSS does not tell us what happens if the user enters incorrect data.

System: Online Banking System (OBS)

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details of the transfer.

- User enters the requested details.

- OBS requests for confirmation.

- OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance.

Use case ends.

Extensions are "add-on"s to the MSS that describe exceptional/alternative flow of events. They describe variations of the scenario that can happen if certain things are not as expected by the MSS. Extensions appear below the MSS.

This example adds some extensions to the use case in the previous example.

System: Online Banking System (OBS) Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money Actor: User MSS: 1. User chooses to transfer money. 2. OBS requests for details of the transfer. 3. User enters the requested details. 4. OBS requests for confirmation. 5. User confirms. 6. OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance. Use case ends.

Extensions:

3a. OBS detects an error in the entered data.

3a1. OBS requests for the correct data.

3a2. User enters new data.

Steps 3a1-3a2 are repeated until the data entered are correct.

Use case resumes from step 4.

3b. User requests to effect the transfer in a future date.

3b1. OBS requests for confirmation.

3b2. User confirms future transfer.

Use case ends.

*a. At any time, User chooses to cancel the transfer.

*a1. OBS requests to confirm the cancellation.

*a2. User confirms the cancellation.

Use case ends.

*b. At any time, 120 seconds lapse without any input from the User.

*b1. OBS cancels the transfer.

*b2. OBS informs the User of the cancellation.

Use case ends.

Note that the numbering style is not a universal rule but a widely used convention. Based on that convention,

- either of the extensions marked

3a.and3b.can happen just after step3of the MSS. - the extension marked as

*a.can happen at any step (hence, the*).

When separating extensions from the MSS, keep in mind that the MSS should be self-contained. That is, the MSS should give us a complete usage scenario.

Also note that it is not useful to mention events such as power failures or system crashes as extensions because the system cannot function beyond such catastrophic failures.

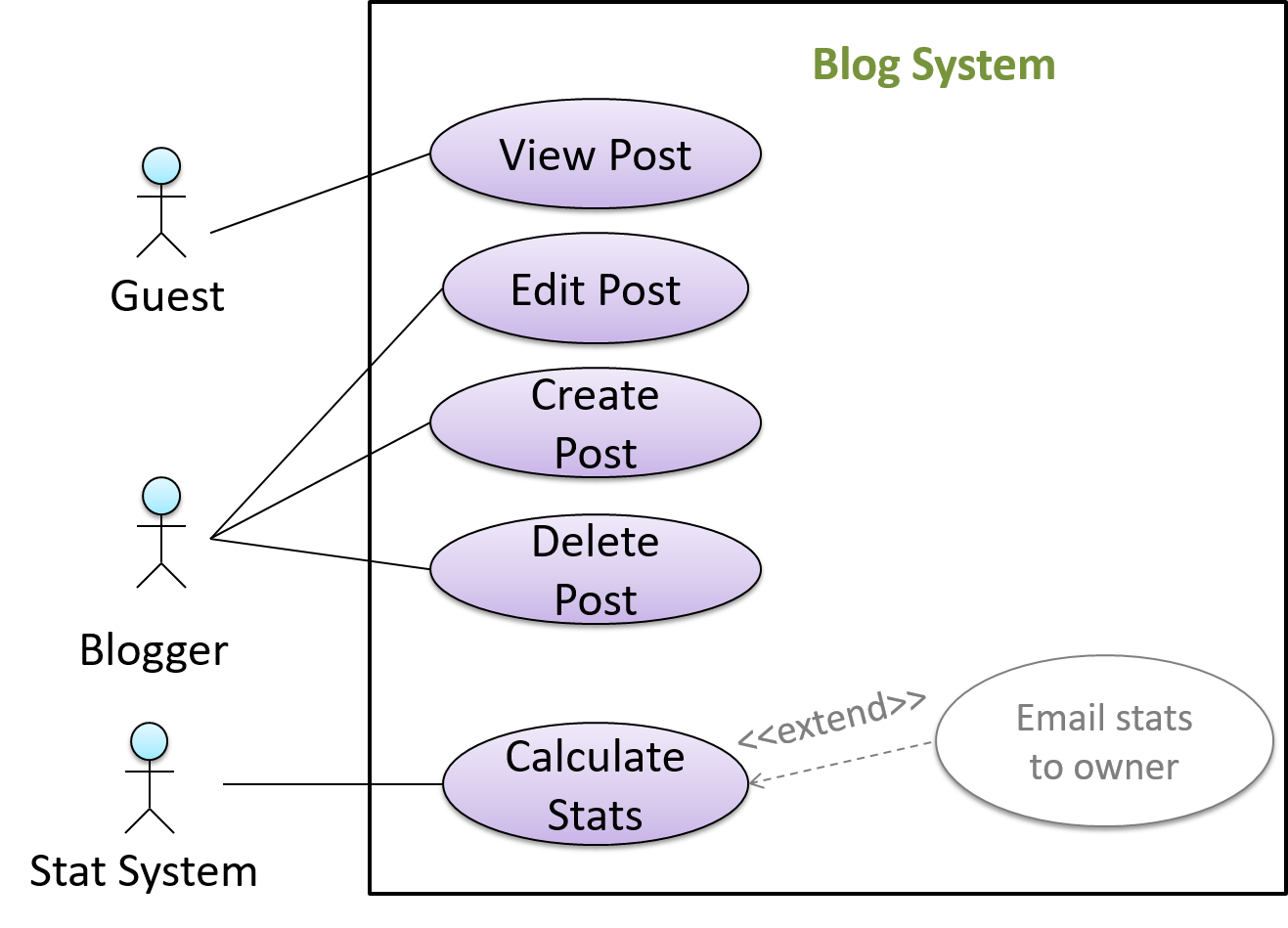

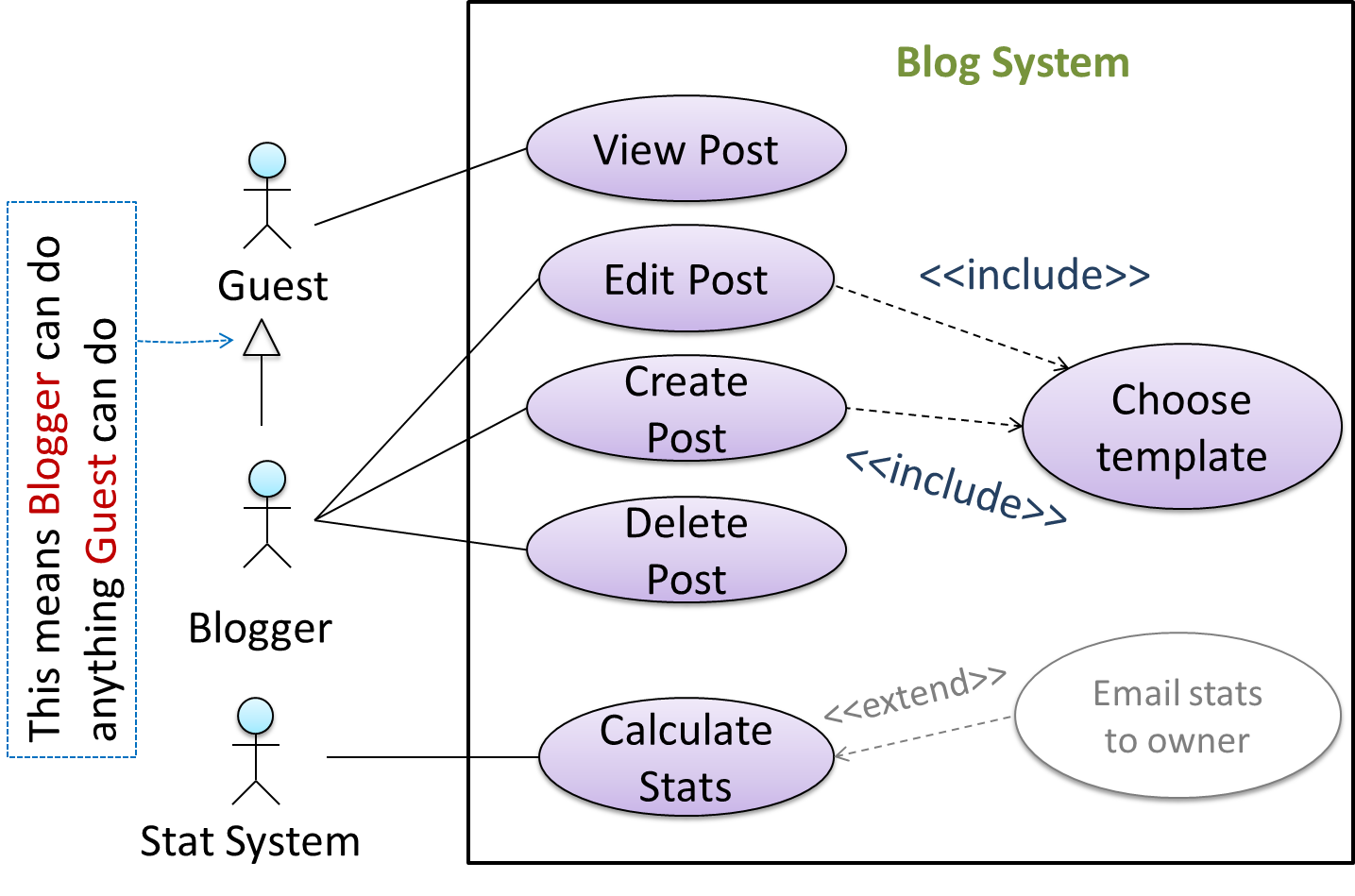

In use case diagrams you can use the <<extend>> arrows to show extensions. Note the direction of the arrow is from the extension to the use case it extends and the arrow uses a dashed line.

A use case can include another use case. Underlined text is used to show an inclusion of a use case.

This use case includes two other use cases, one in step 1 and one in step 2.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Use case: UC01 - Conduct Survey

- Actors: Staff, Student

- MSS:

- Staff creates the survey (UC44).

- Student completes the survey (UC50).

- Staff views the survey results.

Use case ends.

Inclusions are useful,

- when you don't want to clutter a use case with too many low-level steps.

- when a set of steps is repeated in multiple use cases.

You use a dotted arrow and an <<include>> annotation to show use case inclusions in a use case diagram. Note how the arrow direction is different from the <<extend>> arrows.

Preconditions specify the specific state you expect the system to be in before the use case starts.

Software System: Online Banking System

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

Preconditions: User is logged in

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details for the transfer.

...

Guarantees specify what the use case promises to give us at the end of its operation.

Software System: Online Banking System

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

Preconditions: User is logged in.

Guarantees:

- Money will be deducted from the source account only if the transfer to the destination account is successful.

- The transfer will not result in the account balance going below the minimum balance required.

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details for the transfer.

...

You can use actor generalization in use case diagrams using a symbol similar to that of UML notation for inheritance.

In this example, actor Blogger can do all the use cases the actor Guest can do, as a result of the actor generalization relationship given in the diagram.

Do not over-complicate use case diagrams by trying to include everything possible. A use case diagram is a brief summary of the use cases that is used as a starting point. Details of the use cases can be given in the use case descriptions.

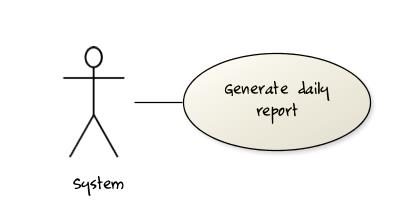

Some include ‘System’ as an actor to indicate that something is done by the system itself without being initiated by a user or an external system.

The diagram below can be used to indicate that the system generates daily reports at midnight.

However, others argue that only use cases providing value to an external user/system should be shown in the use case diagram. For example, they argue that view daily report should be the use case and generate daily report is not to be shown in the use case diagram because it is simply something the system has to do to support the view daily report use case.

You are recommended to follow the latter view (i.e. not to use System as a user). Limit use cases for modeling behaviors that involve an external actor.

UML is not very specific about the text contents of a use case. Hence, there are many styles for writing use cases. For example, the steps can be written as a continuous paragraph.

Use cases should be easy to read. Note that there is no strict rule about writing all details of all steps or a need to use all the elements of a use case.

There are some advantages of documenting system requirements as use cases:

- Because they use a simple notation and plain English descriptions, they are easy for users to understand and give feedback.

- They decouple user intention from mechanism (note that use cases should not include UI-specific details), allowing the system designers more freedom to optimize how a functionality is provided to a user.

- Identifying all possible extensions encourages us to consider all situations that a software product might face during its operation.

- Separating typical scenarios from special cases encourages us to optimize the typical scenarios.

One of the main disadvantages of use cases is that they are not good for capturing requirements that do not involve a user interacting with the system. Hence, they should not be used as the sole means to specify requirements.

Glossary: A glossary serves to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the noteworthy terms, abbreviations, acronyms etc.

Here is a partial glossary from a variant of the Snakes and Ladders game:

- Conditional square: A square that specifies a specific face value which a player has to throw before his/her piece can leave the square.

- Normal square: a normal square does not have any conditions, snakes, or ladders in it.